Funnily enough for something that may or may not have been made up, the meaning of my name was inspiring to me. Whenever I was (and sometimes still am) afraid, I would just remind myself that I'm a woman of courage (even when I was still actually a girl). I think it made me a little bit braver.

I think that life requires a lot of courage--a lot of attempting things that you're not sure if you can do, like taking a french language exam or changing the lights on your car or submitting papers to journals. It takes a lot of courage to do things in which your success is not assured--you're giving someone else the chance to reject you. Well I've done that about a million times, and succeeded once or twice.

The main thing that I'm trying to say is that I think that courage applies to women every bit as much as it applies to men. I'll take a roundabout way of saying that, though.

What exactly are we talking about when we talk about manliness? And is it just for men? I think that people who bemoan the erosion of manliness in contemporary society are referring to ancient ideals such as the pursuit of courage, virtue and honor (which is most often, although not exclusively, evidenced through bravery in battle in the ancient world).

Plato talks about spiritedness (thumos) as one of the three parts of the soul--it is the part of the soul that, like a soldier, defends a country or a person. He is clear, however, that spiritedness alone is next to worthless; it needs to be guided by reason in order to defend the right things.

Aristotle writes, similarly, about the virtues, praising courage as among the highest virtues. Considering courage in the context of virtue, of course, means that Aristotle isn't referring to having courage in any situation, but rather having it in the appropriate amount in the appropriate situation.

Of course, honor is at the center of The Iliad--however, Homer is certainly problematizing Achilles's pursuit of honor. While Achilles bends over backward to protect his property (including his woman war-prize) and to gain recognition from the gods, his pride consumes him.

Harvey Mansfield, in his book, Manliness, is modest in his defense of manliness--"Manliness ... seems to be about fifty-fifty good and bad." While writing against contemporary gender neutrality, Mansfield is attentive to examples of women being manly--for instance, he lists Margaret Thatcher as his first example of manliness.

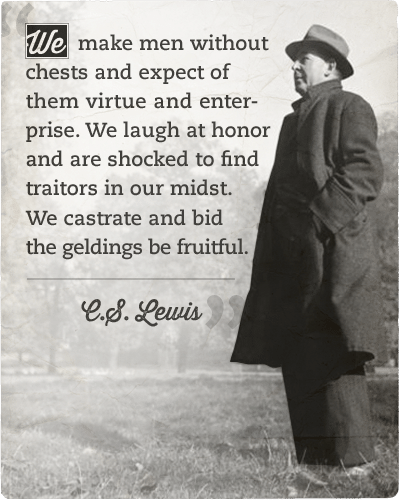

Above: from The Art of Manliness, not my favorite website (especially insofar as it presents a monolithic understanding of what it means to be a man).

This quote is used on that website to supposedly show something about manliness. In my opinion, this shows what's wrong with appeals to manliness--what C.S. Lewis is talking about in The Abolition of Man isn't manliness at all, it's actually about the need for humans to have moral sentiment and reasoned emotion. He speaks about man in the sense of humanity, not man in the sense of being male--Lewis is arguing that moral sentiment, emotion, and spiritedness should be an integral part of every human life. We should all have the ability to engage in moral reasoning and to make distinctions between right and wrong. He advocates such moral reasoning against relativism (or the idea that the only thing you have is your feelings and so no point from which you can judge someone else's feelings), building a theory of natural law in the process. It wouldn't makes sense for C.S. Lewis to argue that only men should engage in moral reasoning, that women should succumb to relativism.

Gendering spiritedness and virtue and courage and moral sentiment and emotional reasoning seems to me to be a problem in several respects. First, it can lead us to praise things that aren't unabashedly good, such as war, hunting, sports. There are benefits to hunting and sports, I bet (war at best is a necessary evil), but there are also downsides. Sports (for instance, football) can be incredibly dangerous, especially when engaged in at the professional level. Teaching at a D1 school, I see the way in which sports take seriously away from academics. Hunting, especially when separated from eating the animal, can degenerate into a bloodthirsty entertainment. Obviously, spiritedness is good when a country needs to be defended, but dangerous when it calls us to more quickly enter into a war than we need to (or, in the case of The Iliad, fight all the time for almost no reason at all).

Another problem with gendering manliness is that it can denigrate men who don't follow sports scores as if their life depended on it (I can't think of a more moronic thing to be obsessed with, myself) or like to kill things. What about the sensitive artist or the bumbling academic? (Both stereotypes that I prefer to the growling Tarzan.) Portraying one view of what it means to be a man is dangerous: clearly not every man can fit into one mold (nor should every man wear one type of outfit; incidentally, looking to the internet to tell you how to dress strikes me as distinctly unmanly). Praising one certain view of manliness downplays other men's experiences and strengths.

Another problem with gendering manliness is that it can denigrate women whose strengths are in the area of courage. It can discourage women from acting bravely or courageously by setting up social norms that push men toward courage and women toward babies (incidentally, I'm convinced that babies need men and women to care for them, not just women).

The idea that men are aggressive and women are passive is based on a very simplistic notion of sex. From experience and from history, we can see that aggression and passiveness aren't strictly split among males and females. I'm not saying that gender difference doesn't exist at all, just that it isn't absolute: male and female bodies are different, and it's quite possible that these differences can have a bearing on the person as a whole, since the body and soul are intimately connected (this is Edith Stein's point).

I am inspired by courageous women--by Deborah and Esther and Antigone and Tecmessa and Lysistrata and Joan of Arc and Edith Stein and Corrie Ten Boom. These women aren't perfect, but I admire their spiritedness and their courage. Much of my life has been oriented to being taken seriously along with the guys. It hasn't been easy, and it certainly isn't easy to mesh that with being a wife, but I think that everyone, man and woman, is called to the virtue of courage, and is called to develop that courage in accordance with reason. (And, on the flip side, I think that every man and woman is also called to kindness and gentleness and caring.)

P.S. How is this manly soap? Can only men make it? Or can only men use it? Or is the problem that "[m]ost soaps out there are designed for the ladies and have foo-fooey scents"? I'm not sure what "foo-fooey" means, but since I hate scented soap, does that make me "manly"? Also, it seems like "foo-fooey" is a little condescending. What if I did like foo-fooey scented soap? What if I were a man who liked scented soap--does that break some rule? Etc.

P.P.S. The other problem with arguing that we need more manliness, and which I didn't address here, but will perhaps address another day, is that Christianity is an important intervention into the ancient idea of virtue: Christianity introduces faith, hope and love as virtues; it introduces humility. It is really a fundamental critique of the spiritedness that so easily becomes pride. The lives of David and Jesus offer an alternative type of courage--the courage that is required to be humble.

5 comments:

But is every feat of courage on a level - submitting an article to a journal, and soldiering in a war? Or do some require more risk than others? The worst outcome of a journal submission is rejection, then submission to another journal. The worst outcome of soldiering?

If the risks prove greater, then will men be more likely to pursue them, but often stupidly, or aggressively and unreasonably? I don't know about the Art of Manliness b/c I never read it, but Aristotle's presentation of moral virtue in the Ethics seems to presume and then try to contain or channel the natural aggressiveness of men into a more considered and civilized character. Courage comes first among the virtues, and it's the least reasonable. Everything afterwards is a constraint on crazed Conan the Barbarian-type courage - moderation, liberality, justice, gentleness, wit, friendliness.

I think Jean Elshtain has written that the Ethics is directed wholly at men and so presumes that virtue doesn't apply to women, but I think that's not quite right. Aristotle says in the Politics that "a man would be thought a coward if he had no more courage than a courageous woman" (but the reverse for moderation) - there are different natural inclinations, and they must be cultivated (strengthened, weakened, channeled) differently by education. Education is for all citizens, and isn't very sensitive to individual differences, like very aggressive girls, or very modest boys, but I don't see where Aristotle and especially Plato rule that out (the individual variation argument is, after all, the argument that persuades Socrates' interlocutors in the Republic to allow female guardians).

Thanks, MSI. You're right--not all courage is on the same level. It also seems like the most risky things to do are not always (or even most often) the best (although, clearly, at times, very risky things are necessary, and so we need people ready to do them).

What you say about courage in the Ethics is helpful. And, yes, education is obviously better if it's sensitive to individual differences. Perhaps one way to accommodate that is being attentive to gender in education, although that creates difficulties of its own. I think my own role as an educator is at its best when I'm attentive to particularity.

Unrelatedly, because it was perhaps unclear, I mean in no way to denigrate having babies, nor the courage that that takes, nor the arrangement that a particular family determines is the best arrangement for them to care for and provide for their family. I mean to question the dichotomizing and absolute gendering of courage and child rearing--the separation of the two and the idea that one is appropriate for each gender.

Emily, I so appreciated this post. It reminds me of Aquinas's insistence on the unity of the virtues. We can't remove one from our picture of the virtuous man or the virtuous woman, and still call that person truly virtuous. This is especially true of courage (aka fortitude, in the Cathechism of the Catholic Church), which is one of the cardinal virtues and should therefore be central to the moral life of all persons, whether male or female. Courage in the Catholic Christian view is not just about lack of something (fear), but also about the presence of something, namely an appropriately firm and constant commitment to the good. Maybe the best way to phrase this is to say that lack of fear (whether of death or another obstacle to the pursuit of the goods appropriately central to the moral life) is a symptom of courage, which most fundamentally consists in an unwavering dedication to the good.

1808: "Fortitude is the moral virtue that ensures firmness in difficulties and constancy in the pursuit of the good. It strengthens the resolve to resist temptations and to overcome obstacles in the moral life. The virtue of fortitude enables one to conquer fear, even fear of death, and to face trials and persecutions. It disposes one even to renounce and sacrifice his life in defense of a just cause. 'The Lord is my strength and my song.' 'In the world you have tribulation; but be of good cheer, I have overcome the world.'"

-EL

PS- The word I have to type in to prove I'm not a robot is "convert." Ha.

EL: Thanks! Hilarious that your response is more Catholic than my post:)

Also--I think you're right--to talk about courage requires us to discern and be committed to the good.

Post a Comment